Lewis &

Clark

Both Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were players in the search for the bones of the American monster.

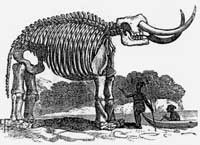

Prior to the departure of their expedition, Lewis traveled to Philadelphia where he viewed the great beast's skeleton at Charles Willson Peale's museum.

Instructed by President Jefferson to look for living "mammoths" in the western wilderness, Lewis was also shown the animal's giant grinders.

As he journeyed down the Ohio River to meet Clark, Lewis stopped at Big Bone Lick to excavate bones. Unfortunately, the specimens he sent to Jefferson were lost when the boat carrying them capsized on the Mississippi River.

To Jefferson's chagrin, Lewis and Clark found neither bones nor living mammoths during their expedition's trek across the continent.

However, the year after they returned to Washington, at Jefferson's request, William Clark returned to Big Bone Lick while in route to St. Louis to become Superintendent of Indian Affairs.

With the help of ten hired laborers, he dug up some three hundred bones that were shipped to Washington and later laid out on the floor of a room at the White House.

"As is evident from the head teeth and paws of the mammoth, it must have been carnivorous," Clark wrote to Jefferson.

The Lewis and Clark expedition coincided with a curious change in the mounting of Peale's skeleton. While they were gone, Peale remounted the tusks on his skeleton pointing downward to emphasize the animal's carnivorous nature.

By the time the explorers returned, Peale's skeleton stood as a monument to the domineering attitude that led to the conquest of the American West.

For the full story of Peale's skeleton and the Lewis & Clark connection, see my article in the electronic journal Common-Place published in January 2004.

READ American Monster

Discover the curious link

between patriotism and prehistoric nature

© 2003 Paul Semonin

In

1803, when Lewis visited

Philadelphia, Peale's skeleton

was mounted with its tusks

pointing upward.

Three

years later,

when Lewis & Clark returned,

the tusks were reversed,

and remained so for

at least another decade.

Peale's original skeleton

can be seen today in the

Hessisches Landesmuseum

in Darmstadt, Germany